Scioto County is at a crossroads—and local leaders say it’s time to grab the wheel and steer economic development back on track.

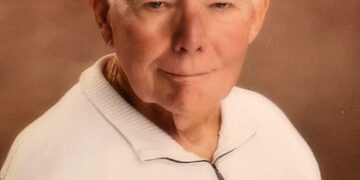

At Thursday’s Commissioners Meeting, Commissioner Bryan Davis didn’t mince words.

“Our economic development has been nonexistent for two months,” he said. “I know SOPA is reorganizing, but we don’t have a ship or a captain. I feel like we need to develop a plan.”

The county’s economic growth has been stalled in the wake of the Robert Horton scandal that rocked the Southern Ohio Port Authority (SOPA) and shook public trust. With no economic development director and SOPA only beginning to pick up the pieces after nearly a year of dormancy, the path forward remains uncertain.

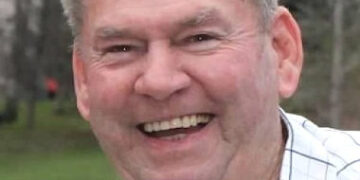

Commissioner Scottie Powell echoed the concern.

“I wish I had an update,” he said at the March 27 meeting. “It’s a tough proposition when there’s still potentially other things coming down the road. The last thing we want to do is build a system around something that could fall apart because of new news. That gives me pause.”

Still, Powell is hopeful. He’s been researching what economic development looks like in other counties and thinking about how Scioto County might create a model that’s built to last.

“A lot of organizations are willing to move forward,” he said. “I’ve been spending this time researching what it could and should look like.”

At Thursday’s meeting, Davis called on Powell and fellow Commissioner Cathy Coleman to share their visions for the future. He stressed the urgency of the moment, noting regional economic concerns like the closing of the Pixelle paper mill in Ross County.

“Now is not the time to retract on economic development. We need to make sure we have someone at the helm,” Davis said. “Yes, we work with regional partners, but we can’t depend on them to do what we should do for ourselves.”

He also expressed concerns about the county operating on a “barebones” structure and called for teamwork to address internal loss control issues.

Powell suggested holding a summit to “reimagine what economic development looks like in Scioto County,” bringing all the key stakeholders to the table.

“How do we pull in Shawnee State, the Technical School, and Community Action?” he asked. “We’re going to get another shot at this. What should it look like?”

Powell acknowledged that SOPA’s reputation has taken a hit and questioned whether it should continue to be the county’s economic engine.

“Throwing things back together the way they were won’t restore public confidence,” he said. “There’s no value in reliving the past.”

He floated the idea of either a public meeting or smaller, private discussions with stakeholders.

“When the cameras are on, people tend to pull their comments. I’m open to both,” he said.

Commissioner Cathy Coleman was on board with the idea of a summit.

“I like the idea of getting different opinions,” she said. “Would we host the meeting? It has to start somewhere.”

Davis agreed, but emphasized that action must follow discussion.

“I’m fully in support of gaining input from the community. But at the end of the day, we have to lead,” he said. “We gotta move fast. There are companies looking to invest in our community right now, and we gotta lead that charge. SOPA is not able to do that right now. They are working hard to get things rolling. We do have two seats to fill on the board.”

The Scandal That Stalled Growth

The Robert Horton corruption case sent shockwaves through Scioto County and brought economic development to a grinding halt. Horton, the county’s former economic development director and SOPA head, was indicted on 15 counts on Valentine’s Day. His wife, Lioubov Horton, faces 12 charges of her own.

The list of charges reads like a true crime headline:

- Theft in office

- Aggravated theft

- Money laundering

- Bribery

- Tampering with public records

Prosecutors say the couple and three unnamed co-conspirators created a fake business to siphon funds from SOPA and the Minford Emergency Ambulance Service. Horton allegedly funneled bribes through his wife, disguised as commission payments, and later instructed businesses to destroy evidence when the Ohio State Auditor began digging.

The fallout has left a leadership vacuum and a serious trust deficit—one that Scioto County officials now hope to overcome with transparency, collaboration, and a long-term vision for sustainable growth.

Next Steps: A Summit for Solutions?

Will a county-wide summit lead to a bold new strategy—or more delays? The commissioners seem aligned on one thing: the time for waiting is over.

“We gotta move fast,” Davis said. “It’s time to lead.”